Let’s go through the Panama Canal

We are sailing our 10-metre sailboat through the Panama Canal, a masterpiece of engineering that connects the Atlantic Ocean in the north with the Pacific Ocean in the south. After having a wonderful time in the Caribbean and Panama, we are continuing our journey. We have never sailed through locks before, so it is all the more exciting for us that our first canal is the world-famous Panama Canal. We were accordingly excited, but first things first.

In this blog post, you will find:

Our transit with Vaquita

Route from the Atlantic to the Pacific

Day 1 - Shelter Bay Marina to lake Gatún:

Locks of Gatún: 3 locks going upwards (26 m)

Distance: 6 nm

Time: 2 hours 45 minutes

Overnight stay in Gatún Lake at a mooring buoy

Day 2 - Lake Gatún to anchorage Las Brisas:

Pedro-Miguel lock: 1 lock downwards (9,5 m)

Miraflores locks: 2 locks downwards (16,5 m)

Distance: 35 nm

Time: 8 hours 55 minutes

Preperations for the Panama Canal

A few days before our canal appointment, our agent brings us six large fenders and four long, buoyant lines. In order to cross the Panama Canal, in addition to the captain, you need four so-called line handlers, i.e. people who operate the lines during the lockage process and thus keep the ship in position. There is also an advisor on board who communicates with the canal and lock personnel and gives instructions on what we need to do. So there are a total of six people on our small boat during the transit. We were lucky and found three other sailors to help us as line handlers: Onno from Canada and Ilya and Marley from the USA (otherwise we would have had to pay professional line handlers).

It is not until the afternoon of the day before our appointment that we find out what time we will be starting tomorrow. As expected, it is a two-day passage and we do not have an appointment at the first lock until 6 p.m. So we still have some time to prepare everything. We do some laundry, prepare food and tidy up the boat.

On the day of the canal passage, we meet at 2 p.m. on board with all the line handlers – after all, we don't know each other at all. But everyone quickly gets along very well and Onno shares with us his experiences of the canal passage he has had so far. We can either go through the locks together with one or two other sailing boats, in which case we have to moor together. The boat with the most powerful engine is then in the middle and the others on the outside. Alternatively, we may be towed by a tugboat, which normally manoeuvres large ships into the locks, or we may go through the locks alone.

We are scheduled to be in the anchorage at 4:30 p.m., because that's when the advisor will come on board. So we cast off at around 3:45 p.m. and sail out of the marina to the anchorage at the specified coordinates, where we drop anchor. Since we still have some time, we have a few snacks and chat.

Gatún locks

The advisor is a little late, but then the pilot boat finally arrives, pulls up precisely on the port side of our boat, and with a practised stride, the advisor Luis steps onto the deck. I immediately weigh anchor and get not only myself but the entire foredeck muddy. The anchorage is obviously completely muddy, and we pull up all the dirt between the links of the anchor chain. The chain (and I) have never been so dirty before. Unfortunately, there is no time to wash the chain – that will have to wait until we reach the Pacific. At least I quickly wash my feet and hands in the water. On the way to the Gatún Locks, we pass the Puente Atlántico, the Atlantic Bridge. It is a cable-stayed bridge that was built in 2019 and replaces the ferry that was used before. With our 15-metre-high mast, we pass through the 75-metre-high bridge without any problems. Shortly after the bridge, we arrive at the lock entrance.

Today, we are the only sailing boat passing through the canal, which means we have to operate all four lines (if we had been passing through with other boats, we would only have had the lines on one side). Canal employees are standing at the canal wall, shooting the auxiliary lines on board using monkey fists (knots used to weigh down the end of a throwing line). We then tie a knot in our blue floating lines, sail to our final position in the canal and stop behind a large Portuguese tanker. There we lower thick blue lines into the water, the canal workers pull them up, wrap them around a bollard and we then pull the lines tight. Then the lock gates behind us close. Like in a whirlpool, water flows into the chamber from below. We have to keep pulling the lines to keep them taut so that the boat doesn't move – sometimes not so easy. After we have been lifted about 10 metres, the gates at the front open and the container ship in front of us slowly moves into the next lock. Then the canal staff throw the blue lines back into the water (the auxiliary line is secured again) and we slowly continue on our way. The canal staff climb the steps to the next higher lock wall and, in our final position, wrap the blue line around the bollard again. And already the gates are closing behind us again, the water is filling up and we are going even higher. The process is repeated a third time. In the meantime, it has become dark, but the canal is well lit. After the third lock, we are 26 metres higher than in the Atlantic and leave it to enter the artificially created Gatún Lake.

Overnight stay in Lake Gatún

We follow the green and red illuminated buoys for a short while before turning to starboard and mooring for the night at a buoy that is much too large for us. We heat up the pre-cooked chilli con carne and make some rice to go with it. Our advisor is picked up again by a pilot boat while the five of us make ourselves comfortable on board. But instead of going to bed early, we discover a cockroach in the saloon, and it takes us an hour to catch it with a glass. After thinking long and hard about what to do with the cockroach, we give it some alcohol before throwing it overboard. Now everyone can go to bed with peace of mind.

Crossing Lake Gatún

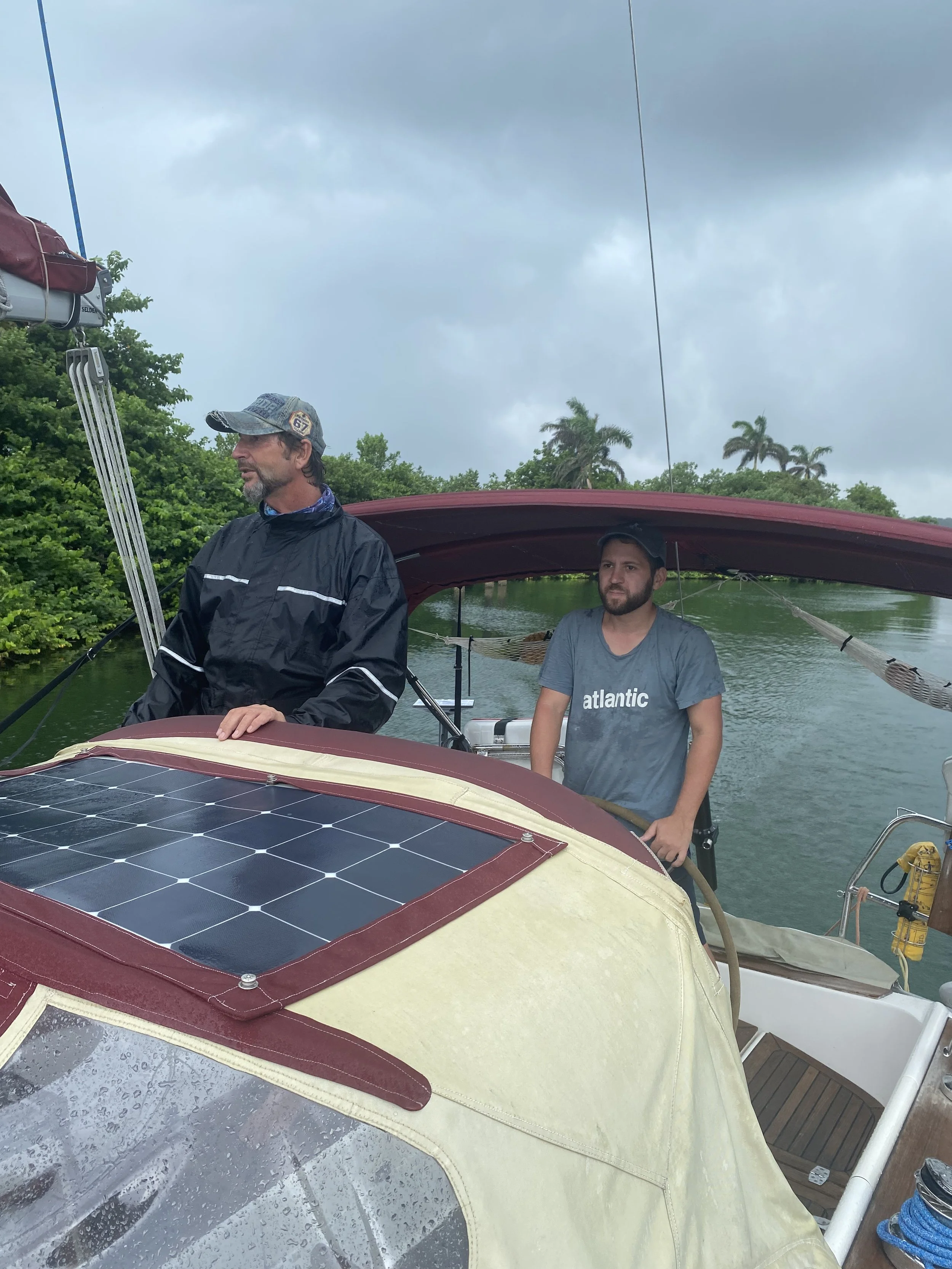

The next day, we get up at 6 a.m. because our new advisor is due to arrive at 7 a.m. We quickly make breakfast – fried bacon with fried eggs and toast – and enjoy the peace and quiet of Gatún Lake, interrupted only by a few howler monkeys and birds. Once again, he arrives a little late, but that gives us time to wash up after breakfast. Immediately after our advisor Romolo comes on board, we cast off from our mooring buoy. Now we have an approximately 5-hour motorised journey ahead of us – sailing is prohibited in the canal – before we reach the next lock. We have to stay as far to the right as possible, i.e. as close as possible to the canal buoys, so as not to get in the way of any larger boats. Our advisor keeps a constant eye on the traffic and today's plan. He asks us to sail faster than our normal cruising speed of 4.5-5.0 knots, so we push our engine to 2400 rpm (instead of the usual 2000 rpm). The weather is a bit mixed, but it's only drizzling here and there. This allows us to enjoy the trip through the man-made Gatún Lake with its small islands and tropical shores. The canal winds its way through the lush greenery and here and there a huge container ship appears around a bend.

Then the canal narrows and we sail from Gatún Lake into the so-called Culebra Cut. Here, the mountain was blasted away to create an access route for ships. Originally, it was even narrower, but it was widened during the expansion of the Panama Canal (2007-2016). We stay as far to the right as possible again, because a freighter is coming towards us. It is impressive to see the huge ships so close. At the end of the Culebra Cut, we pass under the Puente Centenario bridge and then arrive at the next lock, the Pedro Miguel Lock.

Pedro Miguel lock

As on the previous day, we are thrown two monkey fists each, first from the port side and then from the starboard side. We tie the auxiliary lines to the large mooring lines with a knot and enter the lock. This time, we are in front of our large neighbouring ship in the lock and still behind it. As it will be another 45 minutes before it arrives, we use the time to eat the burritos we have already prepared. Lunch in the middle of a lock on the Panama Canal – this is definitely one of the most unusual places we have ever eaten.

In the meantime, my family has not only prepared dinner at home, but also set up the laptop. They are following us via the channel's live stream.

When our big neighbour finally arrives, we get started. The water is slowly pumped out and we gradually let out more rope to keep the boat in the middle. This is definitely easier than pulling the rope the day before. When we reach the final level, the lock gates open again. As soon as they are fully open, the canal staff throw the lines from the lock walls into the water, we quickly retrieve them and continue on to the next lock. This is not immediately afterwards, but about a nautical mile away.

Miraflores locks

After crossing the small dammed Miraflores Lake, we arrive at the Miraflores Locks. After this double lock, the Pacific Ocean awaits us. Once again, we are thrown the auxiliary lines, sail to the end of the lock and moor there. The canal's visitor centre is also located here, and there is a grandstand with lots of people standing on it. We wave and everyone waves back. So we not only have fans at home, but also a fan club on site. Since we have some time again before the neighbouring ship is brought into the lock and into position, we take a few more selfies.

We can observe how the ship behind us stops. Unlike us, no one walks alongside with ropes and ties them to bollards; instead, small locomotives (between 4 and 8, depending on the size and weight of the ship) hold the ship in position with winches. The whole operation is coordinated by radio by the pilot, who stands next to the captain on the bridge. The individual locomotives then respond by ringing their bells. It sounds a bit like Christmas when the Santa Claus comes.

Once everyone is in position and the lock gate behind our large neighbour is closed, we start descending again, centimetre by centimetre. Then the lock gate in front of us opens again and we continue straight into the last lock. As the ship behind us also starts moving, we are pushed along by the current it creates. Although Peter has already taken his foot off the throttle, we are still travelling at 2 knots towards the lock gates closed in front of us. Hopefully we will come to a stop in time. We lower all four lines into the water and hope that the canal staff on the wall will quickly pull the lines towards them and lay them over the bollard. Fortunately, everything works out, even though my counterpart was a little slow. The ship behind us also comes to a stop in time.

Welcome to the Pacific

We descend for the last time. Then we are back at sea level and as the lock gates open, we are greeted by a crocodile in the water. We continue a little further until we reach the Puente de los Americas – now we are officially out of the canal and in the Pacific Ocean. We motor a little further and then our advisor is picked up by a pilot boat. From now on, we are only allowed to continue outside the buoyed channel. After two failed attempts to anchor off Playita, we finally anchor on the other side of the island in Las Brisas. The sun is almost setting again. We take Marley and Ilya to the dinghy dock, from where they take an Uber back to Shelter Bay Marina, and then have dinner with Onno on board. It was a long and exhausting day, but we really made it to the Pacific with our Vaquita!

Second transit on Lost Pearl

Two days later, we sail through the Panama Canal again with Onno on his Lost Pearl. This time from the Pacific to the Atlantic. At least we already know what to expect. And yet some things are different. We set off at 4 o'clock in the morning. In the first two locks, we are alone as usual and in the middle of the canal. In the third lock, we moor to a tugboat – this is fairly straightforward and saves us from having to pull on the lines. Then we pass through the Culebra Cut and Lake Gatún again.

Two days later, we sail through the Panama Canal again with Onno on his Lost Pearl. This time from the Pacific to the Atlantic. At least we already know what to expect. And yet some things are different. We set off at 4 o'clock in the morning. In the first two locks, we are alone as usual and in the middle of the canal. In the third lock, we moor to a tugboat – this is fairly straightforward and saves us from having to pull on the lines. Then we pass through the Culebra Cut and Lake Gatún again.

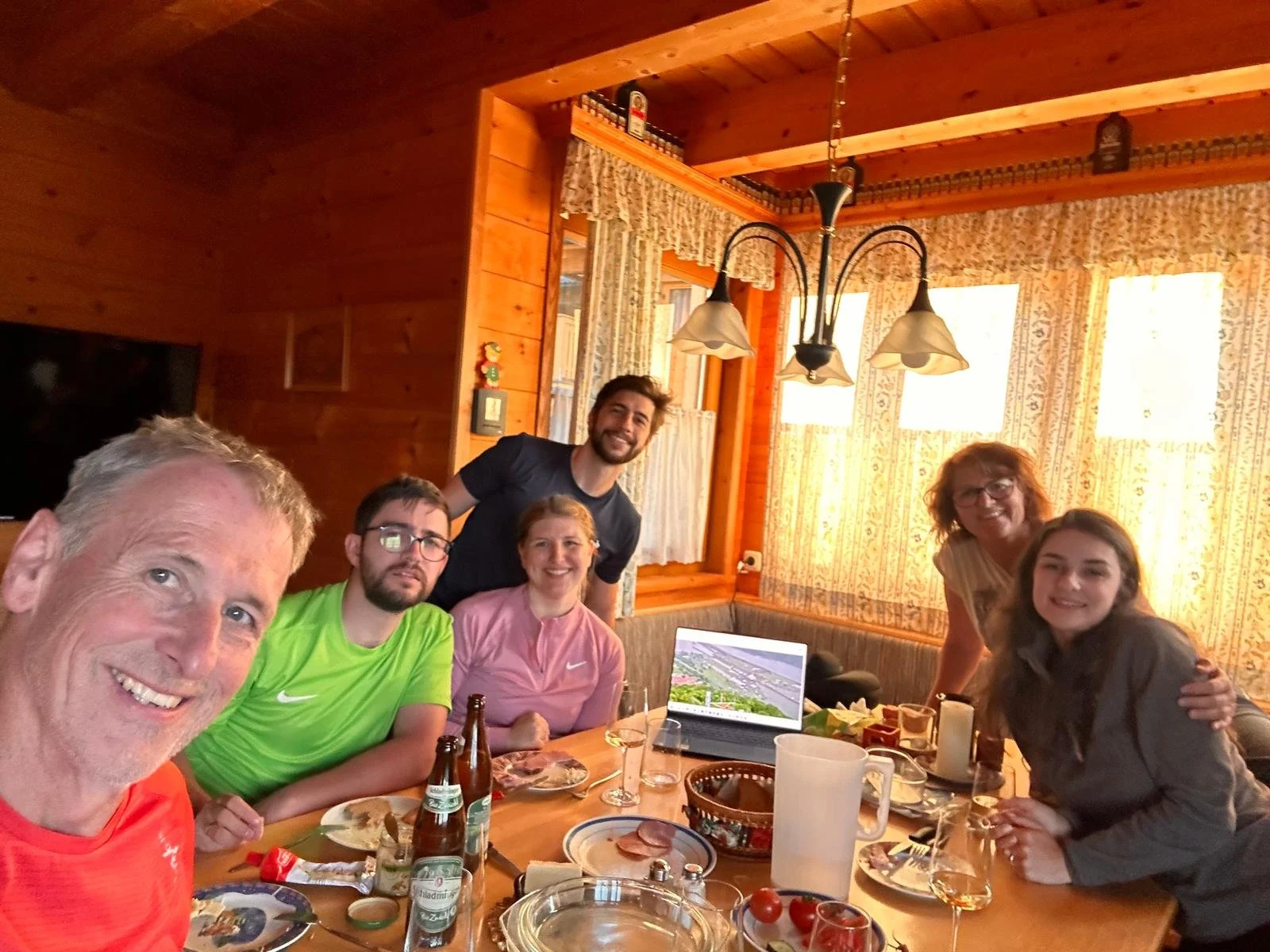

Then we finally make it and dock at Shelter Bay Marina – where we were three days ago. We meet our entire crew – Onno, Ilya, Marley and Marley's husband Jim – on Ilya's boat. We discuss our experiences again, thank them once more for their support and let the evening come to a close.

History of the Panama Canal

Camino de Cruces in blue and Camino Real in red

Evidence of the transportation of goods from the Altlantic ocean to the Pacific dates back as far as 4050 BC but got an increased importance during the Spanish colonization in 1545. The Spanish empire established a network of trails that connected Panama’s Atlantic and Pacific ports, being the Camino Real and the Camino de Cruces the main routes that crossed the Isthmus until the mid 19th century. The Camino Real was a land route used mainly in dry season to transport by mule the “treasures of the kingdom” such as silver, gold and pearls, as well as mail and enslaved people from Africa. The Camino Cruces took advantages of the Chagres River’s lenghty navigable course to transport people and goods in small cargo boats during the rainy season. [1]

The discovery of Gold in California in 1848 sparked a “Gold Rush”, where hundred of thousands of people (mainly from the USA) travelled to California. Due to the lack of infrastructure and security of overland routes, people seeked alternative maritime routes including through Nicaragua, Cape Horn and Panama, with the latter becoming especially popular.

From 1850-1855 a railroad was built between Panama and Aspinwall (now known as Colón) under the direction of U.S. engineers. The workers faced harsh conditions clearing swamps and jungle to prepare the ground for laying a railroad. The finished railraod transformed the dangerous multi-day journey to a safe trip of less than 12 hours. However by diverting the transisthmian trade away from the Chagre River, the railroad disrupted the livelihood of towns that for centuries had depended on providing lodging and transport services to travelers moving along the river. [1]

After the Suez Canal was successfully completed in 1869 under the direction of Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps, he also began construction of the Panama Canal in 1891. The plan was to build a canal at sea level without locks, as had been done with the Suez Canal. However, there were more challenges than expected: tropical diseases in the swampy landscape, blasting of the continental ridge, and landslides that repeatedly filled in the trenches. More than 22,000 workers died in the process—that's more than seven deaths per day. In 1889, the French gave up. [2]

In 1903, the Herrán-Hay Treaty between the US and Colombia on the construction of the canal in what is now Panama, which at that time still belonged to Colombia, failed. The Panamanians were greatly disappointed, and this strengthened their efforts to gain independence from Colombia. With the support of the US, the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty was concluded. In exchange for 16 km of land around the canal, $10 million, and an annual payment of $250,000, the US guaranteed Panama's independence. This meant that a 16 km strip of land around the canal, which runs across Panamanian territory, and other areas deemed necessary, became US territory. Military bases could be built on this territory, and military interventions that the US deemed necessary for defense were also covered. Apart from the above-mentioned payments, Panama was excluded from any future participation in the canal's revenues. The negotiating position of Panama, which did not even exist at the time, was so poor that the US was able to dictate all the terms. The miserable conditions were one reason for the ongoing friction until 1999, when Panama regained control of its territory. [1] However, Panama first gained independence from Colombia in 1903, and the following year, under the leadership of John Frank Stevens and later George W. Goethals, construction work began on a waterway with locks. A 13 km long stretch through the mountain ridge: the Culebra Cut. In addition, an artificial reservoir was created: Lake Gatún. At the time, it was the largest man-made freshwater lake in the world! Gatún Lake is 26 m above sea level, making locks indispensable. The Panama Canal was opened on August 15, 1914. [2]

However, it was not only the imposed treaty with poor participation in the canal's revenues that led to tensions between Panama and the US, but also the racist administration of the canal zone. American citizens belonged to the “gold payroll,” which clearly separated them from the rest of the workers on the “silver payroll.” Not only were the pay rates significantly different, but so were the accommodations, education for children, and access to goods. [1]

All of this was not conducive to effective cooperation. After Panama went through a turbulent period of military dictatorship, various unrest, and several renegotiations with the US—events that are too complex to describe in detail here—Panama was finally able to agree in 1977 to hand over the canal by the year 2000. On the last day of this period, the US handed over the canal to Panama on December 31, 1999. [1]

The volume of freight traffic worldwide, and thus also traffic through the Panama Canal and the size of ships, is constantly increasing. For this reason, additional new locks were built between 2007 and 2016, allowing larger ships, known as Neo-Panamax ships (up to 400 m in length), to pass through. The narrow Culebra Cut was also widened during the renovations. [3]

Quellen:

[1] Museo del Canal Interoceánico de Panamá (Panama Canal Museum)

[2] Die Geschichte des Panamakanals

[3] Panamakanal – Wikipedia

Useful tips:

Transit organization - With or without an agent?

You can organize the crossing yourself or, as in our case, use an agent. If you have time, the former is certainly an interesting option to save a little money. If you don't have that much time, the latter option is probably the less complicated one. In both registration processes you need to choose the lock positions you are comfortable to transit with. Read more about that here.

Panama Canal - No agent procedure

The following is the procedure without an agent (no guarantee), taken from a description by another cruiser from the Noforeignland app. We have met people who have managed it without an agent and have not reported any major problems. Here is the procedure:

1. Register Your Boat

Visit the webpage ACP - ASEM and complete the registration process.

Upload the required boat photos and follow the instructions on the site.

This step can be done in advance.

2. Create a New Visit

Log into the system and create a new visit. ETA should be realistic.

At the end of the process, enter your banking details.

3. Confirm Your Arrival

Once you arrive at the Panama City, update your status in the system.

4. Print Payment Documents

Download and print the required documents for payment from the system.

5. Make the Payment

Go to Citibank in Panama City (Torres de Las Américas, ground floor).

At the entrance, inform security that you are going to Citibank and present your passport.

You will be directed to an elevator that takes you to the bank.

Pay the fee in cash and provide the printed documents.

Obtain a payment confirmation receipt.

6. Upload Payment Confirmation

Take a clear picture of the payment confirmation.

Upload it to the system.

7. Schedule Your Transit

Call the provided number (or the one that was displayed in the system) to schedule your canal transit.

8. Day before crossing call scheduler again to confirm

Panama canal – Procedurce with an agent

The agent costs USD 470 as of May 2025. This includes lines and fenders and handling all communication with the canal authority. Payment is also made to the agent, either in cash or by credit card.

We used Rogelio from Panama Cruiser Connection. This worked very well. He can be reached at +507 6717 6745 via WhatsApp.

Prerequisites

Captain + 4 linehandlers (18 years old at least)

4 lines 125ft each, 7/8” (on smaller vessels no problem to have smaller diameter, it has to fit the cleats)

Fenders should be adequate for boat size. I would advise having at least 4 on each side

Bimini for advisor - shade (not a joke)

Sealed bottles of water for advisor

Be prepared to cook 3 hot meals for advisor, breakfast, lunch, dinner (we crossed 4 times and it was always just 2 meals asked)

Coffee

The boat should be able to reach 5 knots under engine power.

Costs

As of May 2025, for a boat up to 18.5 m (60 feet) long (for larger boats, you need a pilot instead of an advisor, which is correspondingly more expensive).

Transit Toll: 2130 USD

TVI Inspection: 120 USD

Security Charge: 165 USD

Vessel Scheduling Fee: 500 USD

Total: 2915 USD

Additionally, depending on the situation:

470 USD for the agent (includes organization of the canal passage, lines and fenders, and handling of the cruising permit for Panama, if desired)

120 USD per professional line handler

185 USD Cruising Permit forPanama

105 USD Zarpe

20 USD per line

Line handlers

Apart from the captain you need 4 additional line handlers. As mentioned that can be any person over 18 years that is fit to handle a line. That part is actually not to be underestimated. Depending on how the boat is rafted up and the size of the boat it can be hard work that requires speed and routine is helpful. Especially during the busy period (January to April, keep in mind that the World ARC is going through in February) cruisers usually help each other out and rarely all 4 line handlers on each boat need to work, as boats are rafted up together (up to three boats) and only the outer lines of the outer boats are used. Using amateur line handlers is perfectly fine and it worked well for us. However, on our second trip on a much bigger boat we saw what a difference it made to have professionals handling the lines, especially on a larger yacht there is nothing wrong with having at least 1-2 professional line handlers.

Professional line handlers can be obtained via canal agents.

Amateurs can either be personal contacts, where you help each other out or can be found via the Shelter bay line handler group (you can contact Debbie from Shelter Bay to add you to that). It is common practice to pay food and the trip back to the other side for the helpers. A taxi or Uber back is usually around 100 USD.

WhatsApp of Debbie: +507 6418-6407

Lock positioning

On applying for the transit you will be asked on which positions you are comfortable to transit the canal. This can be in center chamber transit, sidewall, nested with other boats and tied up to a tugboat.

Center chamber transit means alone in the center of the chamber. There is nothing wrong with that it requires all line handlers to work and is unlikely to happen in the high season of the canal as only one small boat can transit then at the time. That is how we went through with our boat.

Sidewall transit means that two lines are attached and you go alongside the wall up and down. Having done that on Onno’s boat I wouldn’t recommend it. Especially going up, where there is usually a lot of turbulance the spreaders can hit the wall. It was already daunting going down and we constantly had to make sure the dinghy on the davits did not hit the wall and also the spreaders came quite close to the wall some times.

Nested with other boats is the most likely way you are transiting in the busy period. Depending on the boats you are going through with, it can be from comfortable to crappy. It all depends on how balanced the boats are and we heard all kinds of stories. In most cases it went totally fine though. The boat with the most potent engine is in the middle and responsible for maneuvering. This can be a problem if the weight load of the nested boats is very unbalanced (e.g. light Catamaran in the middle, heavy and big boat on starboard and smaller and lighter boat on port).

Tied up to a tug is also an option we didn’t see anything problematic with. In this case you’re tied up to the tugboat which is alongside the wall, doing all the work. The only tricky part can be if the tugboat wants to leave and go in front of you. In that case you would have to cope with the thrust created by the tugboat and keep the boat straight in the lock.